Slavery at Conjurer’s Neck and Old Brick House

Slavery has it roots in the earliest days of the colonial history of Virginia. Slavery was first introduced into the colony in 1619, when a captured slave ship arrived at Jamestown that “brought not any thing but 20. and odd Negroes”. The slaves dropped off at Jamestown came from Angola. African slavery in this first introduction into Virginia, was not yet an established institution. At this point and on up to about the fourth quarter of the 17th century, indentured servitude was the primary labor source in Virginia.

Indentured servants would be brought over having their passage paid for by plantation owners and would in turn usually serve a term of four to seven years in return for having their passage paid for. They would work for their master performing all sorts of work, including blacksmithing, building, farm labor, domestic housework and numerous other skilled work. In turn, masters would provide room and board and clothing for the term of service. Indentured servitude at times could be just as harsh as race-based slavery, but it was not the same. There was an end in sight. At the end of the term of service, indentured servants would be free to attempt to establish themselves by acquiring land and “making a go of it”. Sometimes, if a servant was lucky, their master would provide them with a small acreage of land that they could start themselves off with.

An interesting story is that of Anthony Johnson. He first arrived in Virginia in 1621, listed in documents as “Antonio a negro”, to work on a tobacco plantation. It is unclear if he was brought to Virginia as an indentured servant or a slave, but after several years of service, he obtained his freedom and had married a woman named Mary on the plantation he served at. He and Mary would go on to have four children and own 250 acres of land in Northampton County, on Virginia’s eastern shore, raising livestock. It was an uncommon occurrence for an ex-servant or slave, even among white former indentured servants, to go on to own their own land. Anthony and Mary would sell their land in 1665 and move to Maryland and lease a 300 acre tract of land. Anthony died in 1670 in Maryland. Though he became a private landowner, in the case of Anthony, race reared it’s ugly head. A court back in Virginia, in the year of Anthony’s death, ruled that because “he was a Negro and by consequence an alien,” the land owned by him in Virginia belonged to the Crown.

Anthony’s story was an exception. Most former indentured servants did not go on to prosper as Anthony did. Though slavery was not the primary source of labor in the early days of the colony, it was used. Later in the fourth quarter of the 17th century, there began a shift from indentured servitude being the primary labor source to slavery. Indentured servitude, though harsh, ended with the promise of freedom. Though indentured servitude did not end, the flow of indentured servants from England began to slow, which allowed for the growth of slavery in Virginia. A shift in economy and society in Virginia also caused this shift. Bacon’s Rebellion, a number of prominent historians have noted, according to Encylopedia Virginia, “was, in part, the result of discontent among former servants. By harnessing that discontent and, in the name of racial solidarity, pointing it in the direction of enslaved Africans, white elites could create a more stable workforce and one that was less likely to threaten their own interests. Other historians have observed that the flow of English servants began to dry up beginning in the 1660s and fell off dramatically around 1680, forcing planters to rely more heavily on slaves. Slavery did not end indentured servitude, in other words; the end of servitude gave rise to slavery.” In 1705, Virginia enacted a series of laws known as the Virginia Slave Codes of 1705 (formerly An act concerning Servants and Slaves). These codes solidified slavery in Virginia and served as the foundation of Virginia’s slave legislation. For more on these codes visit Encyclopedia Virginia, “An act concerning Servants and Slaves” (1705) – Encyclopedia Virginia.

Chattel slavery was the main type of slavery used in the colonies, and later United States. This system was characterized by the treatment of enslaved persons as property, being stripped of their basic human rights, and exploited for their labor. The enslaved were bought, sold, and owned like any other piece of property.

Slavery was a restriction on the ways of life, what one could and could not do and when, who a slave could marry and who they could not marry. It was a harsh institution that worked millions of human beings to a point past exhaustion. In slavery, the condition of children followed that of the mother. If children were born of an enslaved woman, her children were enslaved. Likewise, if children were born of a free black woman, those children were free.

Enslaved people were expected to work in their jobs, whether they were in the fields or in domestic capacities, from sun-up until sun-down. Sometimes, if the moon was full, enslaved people would be required to work in the fields by moon light. Enslavers and overseers of the enslaved labor force were often harsh, and could mete out harsh forms of punishment, even for the slightest of infractions.

The enslaved were expected to work year-round. Some would have time off on Sundays as it was a day of required religious attendance. Early on in Virginia, the enslaved were allowed to gather with other enslaved people and have their own worship services with religious leaders who were themselves enslaved. Some enslaved people on the other hand were made to go to religious services with their white enslavers. In the churches of colonial Virginia, if there were balconies, the enslaved were seated there; if not, they were made to stand in the back during the service. But after events such as Gabriel’s Rebellion and Nat Turner’s Rebellion, enslaved people were further restricted from assembling and having religious gatherings performed by their own preachers; they would have to get religious instruction from white pastors.

The enslaved usually would get a couple or a few days off during Christmas, but not always. Some slave owners did not like to give their enslaved people time off during the holidays because they worried that it would give them a chance to try to escape. Others, such as the household enslaved people and cooks, would likely not have time off during the holidays as they would have to wait on their white enslavers and guests who may be visiting for the holidays.

Enslaved people were clothed and fed. Clothing though was often not comfortable and weather appropriate. Rations given to the enslaved were not sufficient enough of a diet for the work they were expected to perform. In some cases, slave owners would allow enslaved people to use a small plot of land to plant and tend their own gardens to supplement their diets. They would tend to their gardens after long, hard days of work and on Sundays in their leisure time. At Christmas time, sometimes owners would give their enslaved people extra rations.

Sometimes the enslaved would receive gifts during the holidays. At Christmas, enslaved women were usually given a length of low-quality cloth called osnaburg, a rough, course cloth, with which they would make clothing for men, women, and children. Children, a piece of fruit such as an orange. Enslaved men would sometimes be gifted alcohol. Household enslaved people could be tipped by visitors and guests who were waited on by them, but these occurrences were rare.

Enslaved people would use their leisure time to tend to their personal gardens, socialize, play games, play music and dance. Sometimes the enslaved could get passes to go to market and sell some of what they grew in their gardens and any other items such as chickens, eggs, and any other items they produced on their own time. In a few instances, the owners would even purchase items from their enslaved peoples such as fruit or vegetables from their gardens or eggs from their poultry.

The Kennon family of Old Brick House were not known for having kept diaries or journals, and because of official documents lost at the end of the Civil War when Richmond burned, records of slavery at Old Brick House are few and far between. But what information is available, paints something of a picture of the role slavery played at Old Brick House and Conjurer’s Neck.

Richard Kennon and his role in the peculiar institution

The institution of slavery has been a part of Old Brick House going back at least to when the Kennons first settled Conjurer’s Neck. Though his early origins are sketchy, Richard Kennon was in Virginia by 1670. He initially obtained land at Bermuda Hundred and near Rochdale. Kennon had a warehouse at Bermuda where he was engaged as a successful merchant. On October 19, 1677, Richard Kennon purchased Conjurer’s Neck from Christopher Robinson. As well as being a merchant, he was also an agent and attorney for William Paggen and Company, a London merchant heavily engaged in trade with Virginia.

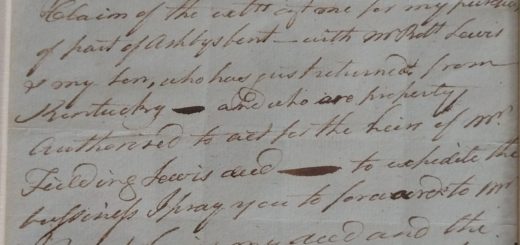

What kind of trade was Paggen engaged in? Tobacco, slaves, rum, sugar, and any other wares he had in his London warehouse. Kennon and a Quaker by the name of John Pleasants both served as agents for Paggen and Company, their role being receivers and sellers of the slaves that Paggen and Company sent to the colony. In a letter dated June 21, 1684 by William Byrd, he writes “Mr. Paggin sent about a fortnight since into these parts, 34 negroes with a considerable quantity of dry goods and seven or eight tons of rum and sugar, which I fear will bring our people much into debt and occasion them to be careless with the tobacco they make.” Kennon and Pleasants made a petition to be exempt from paying taxes on these slaves sent to Virginia. As regards their petition, they were awarded the following from the Henrico County Court:

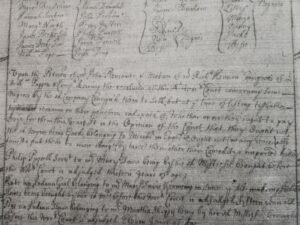

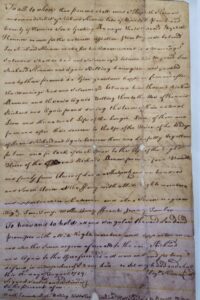

…desiring the resolution of this Right Worshipful Court concerning some Negroes of the said Company consigned them to sell, but at ye time of listing tithables, remaining in their possession undisposed of: It is the opinion of the Court that the said Kennon and Pleasants ought not to pay levy for them this year, because the said Negroes being goods belonging to merchants in England, ought not in any reasonable time to put them to more charge by taxes than other of their commoditites imported hither.

1684 Henrico County Court document, exempting Richard Kennon and John Pleasants from paying levies (or taxes) on enslaved people brought into Virginia. Courtesy Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia. Henrico County Order Book (& Wills), 1678-1693, Reel 53, page 163.

As agents for Paggen and Company, these thirty-four slaves were delivered to Kennon and Pleasants in Virginia to be sold by them. What happened to these slaves is unknown. They were likely sold by Kennon and Pleasants, some of them may even have been purchased by these two men.

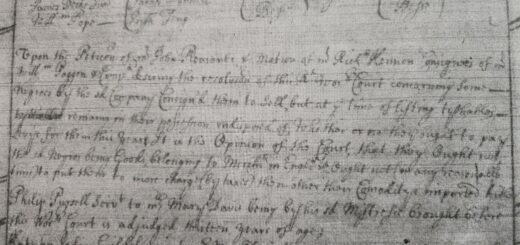

On April 1, 1690, Kennon received a land grant of 8,000 acres for having transported ninety white people and as the land grant states “fifty Negroes at one time & twenty Negroes more at another time.” The grant actually lists all of the indentured servants by name, but not those to be sold as slaves. Under the headright system, for every person brought to the colony of Virginia, whether enslaved or indentured, the person furnishing passage of said persons was to receive fifty acres of land per person (the headright system would be abolished in 1779, during the Revolutionary War). This is one of the ways Richard Kennon was able to amass large amounts of land. Aside from bringing in and selling large numbers of slaves, Kennon also brought in a large number of indentured servants as well.

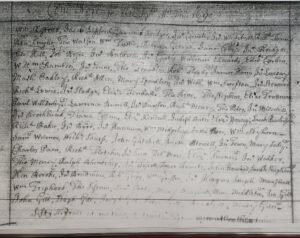

Land grant listing names of 90 indentured servants and 70 enslaved people (not named) imported by Richard Kennon. Courtesy of Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia. Henrico County Order Book (& Wills), 1678-1693, Reel 53, page 327.

April 1, 1690, land grant of 8,000 acres of land to Richard Kennon for importing 90 indentured servants and 70 enslaved people to Virginia. Courtesy Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia. Henrico County Order Book (& Wills), 1678-1693, Reel 53, page 326.

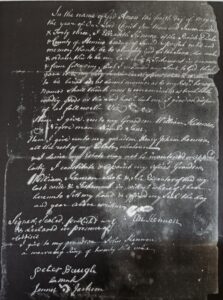

A common occurrence in the era that slavery occurred was for owners to give slaves and land as marriage gifts and when a slave owner made their wills, it was very common for them to devise slaves to their heirs as they would land and livestock. When Richard Kennon made his will on August 6, 1694, he gave “unto my Daughter Judith one younge feemale Negro.” Notice how Richard does not mention the slave by name. It was common that slave owners would not mention a slave by name as it gives them an identity. One of the ways slave owners asserted their dominance over their bondpeople was to take away their identity, any way for them to be an individual, a person.

Richard Kennon’s will, courtesy Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

Elizabeth Worsham Kennon

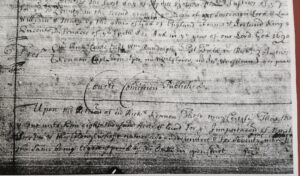

Elizabeth Worsham Kennon, daughter of William Worsham and Elizabeth Littlebury, was the wife of Richard Kennon who purchased Conjurer’s Neck in 1677. Richard died in 1696. Elizabeth likely stayed on the home plantation at Conjurer’s Neck as it was common practice for widows to do so. Widows were entitled to a life interest in a third of their deceased husbands property. In a 1719 deed of gift, Elizabeth granted to her son, Richard and his wife to be, Agnes Bolling, 444 acres of land at “Wintepock”, part of a land grant Elizabeth had received in 1703. This deed of gift also gave them 107 acres of land at a ferry Elizabeth had operated, just a short ways upriver from Conjurer’s Neck. It was a common practice in colonial Virginia to gift enslaved people and/or land as wedding gifts. In the deed of gift, Elizabeth gave Richard and Agnes “Seven negroes Vis. Sam, Tony Moll Amy Frank Jenny Tom boy To have and to hold.”

1719 Deed of Gift, Elizabeth Kennon to son, Richard Kennon and Agnes Bolling. Courtesy Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

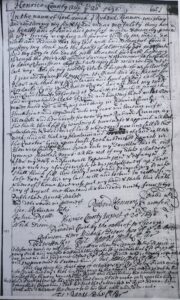

As her husband Richard did, Elizabeth gifted a slave, “my Negroe man Named Saul”, to her grandson, William Kennon in her 1743 will. This was one of the horrors of slavery. Families being split up in wills and sent to other plantations further away from family and loved ones.

1743 Last Will and Testament of Elizabeth Kennon. Courtesy Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia. Henrico County Miscellaneous Court Records, Vol. 4, 1738-1746, reel 2, page 1225.

The Bristol Parish Birth Register

Established in 1643, Bristol Parish served residents of Henrico, and later, Chesterfield County. The main church was located at Bermuda Hundred. This parish was where the Kennons of Conjurer’s Neck attended church services. Elizabeth Worsham Kennon, wife of Richard Kennon—the first Kennon to settle at Conjurer’s Neck—operated a ferry that took parishioners to and from services and she was paid by the parish, in tobacco, for the operation of that ferry. Both of her sons, William and Richard were members of the parish vestry.

The parish vestry maintained a register of births, baptisms and death. This register was believed to have been lost to history but was found in 1894 in the library of Reverend Churchill J. Gibson of Petersburg. In 1898, the register was transcribed and put into print by Churchill Gibson Chamberlayne, The Vestry and Register of Bristol Parish, Virginia, 1720-1789. On page 52 of Chamberlayne’s work is an entry that states, “Eliz: dau: of Rich & Agnis Kennon Born 12 day decem 1720. Harry a negro boy belonging to ditto born Janr 1720.” This is an amazing find. It was not common for enslaved people to be listed in parish records of the colonial era. It was even less common for them to be listed and their date of birth noted. This is not the only instance though of this in the Bristol Parish register. On page 53 and 54 can be found the following:

Negroes Belonging to Majr Wm Kennon

Nutty born 3d octobr 1711.

Pegg born March 18th 1716.

Lewis born 20th Aprill 1719.

Annake born 14th febr 1720.

Hannibal born 17th decem 1722.

Kate born 3d June 1723…

…Negroes Belongine to Majr Wm Kennon.

Hannah female Born 2d June 1723.

Harry male slave Born 1th March 1725.

Phillis female slave Born 1th March 1725.

Scippio male Slave Born 3d March 1727.

Lucy female Slave Born 10th July 1729.

Juno female Slave Born 5th July 1729.

Sampson Male Slave Born 1 decembr 1729.

Phebe female Slave Born 2d Janr 1730.

Sam Male Slave Born 4th January 1730…

…Negro slaves belonging to William Kennon Gentleman.

Daniel male slave Born august 1732.

Cyrus male slave Born July 1733.

Molbrow male Slave Born June 1731.

Cato male Slave Born July 1733.

Prince male Slave Born Dcer 1733.

Adam male Slave Born Dcer 1733.

Jemmy male Slave Born March 1733…

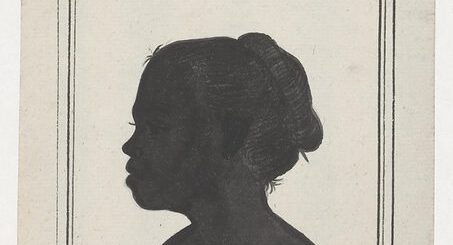

Something that can be gleaned from some of the names of these children (Scippio, Cato, Juno, Sampson, Prince), is a naming pattern. It is important to note that slaves, in almost all instances, did not get to pick the names they gave their children, or their own names for that matter, when they came to the colonies. Many enslavers would name their slaves after Greco-Roman characters, heroes, and authors. Susan Wegner, an Associate Professor of Art History and Chair of Department of Art at Bowdoin College, states that enslavers naming their slaves after “classical names could show off slave-holders’ learning while also mocking those humans held as property by giving them ironic names of powerful ancient rulers, gods, and heroes.” Some of the names enslavers gave to their women bondspeople, like the name Venus for example, “reflected and licensed the lasciviousness of European slaveowners toward African women, making such behaviors ‘sound agreeable,” states Sarah Abel, a cultural anthropologist.

The Bristol Parish register is truly amazing. There are twenty-three enslaved people listed in the register belonging to the Kennon family and their birth dates listed. This is a wealth of information considering how uncommon this is. There are other enslaved people listed in the register that belonged to other families as well. This begs the question, why is it that so many enslaved people, especially those of the Kennon family, turn up in this register? One answer could be that these enslaved children could be the children of household slaves, those who were closest to the family and spent the most time with the Kennons. Perhaps the Kennons felt some sort of affection or fondness for the parents of these enslaved children. Hopefully, future research may turn up more answers.

Cicero, the Baker

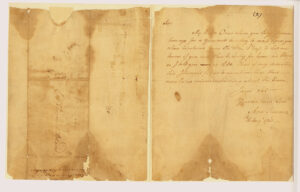

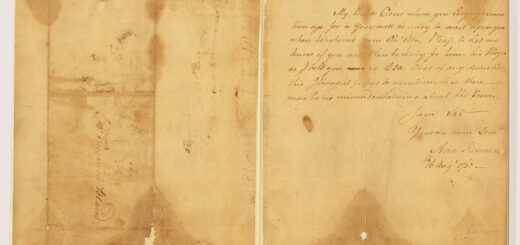

Sir,

My Baker Cicero whom you Engagd some time ago for a Year will be ready to wait upon you when he returns from Ch City, Please do Let me know if you will then be ready for him. his Wages as I told you is £30. Clear of any deduction this I thought proper to mention, that there may be no misunderstanding about the Terms.

I am Sir

Your mo hum Servt

Ann Kennon

th16 Augt 1763

Letter from Anne Hunt Kennon to Theodorick Bland of Cawsons. Image courtesy of Virginia Museum of History and Culture (Mss1B6108 a20), www.virginiahistory.org.

The above is a letter written by Ann Hunt Kennon, wife of Richard Kennon (himself a grandson of the first Richard of Conjurer’s Neck), to Theodorick Bland of Cawsons. The original of this letter is housed at the Virginia Museum of History and Culture in Richmond, Virginia. Richard and Ann lived at Old Brick House, Richard having inherited it from his father, William Kennon. Cicero was the baker for the Kennon family at Old Brick House. As was common with skilled enslaved people, Cicero was rented out to Theodorick Bland for his services. The price of £30 for his labor in 1763 was not a small sum. In today’s U.S. dollars, this would equate to just under $7,600.

Seeing as Cicero had been previously rented out to Mr. Bland, he was likely a very skilled baker. In the colonial era, plantation owners often hosted large elaborate dinners. Guests who came could stay for a day, a few days, or even weeks. This required having skilled cooks and bakers as the meals included multiple courses. Dinners, the largest meal of the day and usually occurred around two or three in the afternoon, included multiple types of meats, vegetables, and desserts.

Though being a baker was a more ideal position to have in a plantation society rather than having to work in a field from sunup to sundown, it was still a tough job. Early on, kitchens were attached to homes, but later, to prevent fires in the main house, kitchens were later built as separate buildings. These kitchens were often hot as a fire was almost always burning in the fireplace and stoves. On a hot summer day, that would have made for an uncomfortable work environment, especially considering enslaved people were clothed in a low-quality textile that was rough and course. The work of being a cook or baker was physically demanding as well. Depending on the demands of the day, cooks and bakers would most often be up before dawn to start preparing the meals for the day.

Enslaved cooks and bakers contributed much to southern foodways which evolved into much of our cuisine of today. Cicero was one of the many enslaved people who helped contribute to the development of those southern foodways. For more information on Cicero, click the following link for an article written about him: https://www.toddsarchives.com/unknown-to-known-how-cicero-gained-his-identity/.

References

Bruce, Philip Alexander. Economic History of Virginia in the Seventeenth Century. New York, NY: MacMillan and Co., 1896.

Chamberlayne, Churchill Gibson. Births from the Bristol Parish Register of Henrico, Prince George, and Dinwiddie Counties, Virginia, 1720-1798. Richmond: Churchill Gibson Chamberlayne, 1898.

Hardin, William Fernandez. “Litigating the Lash: Quaker Emancipator Robert Pleasants, The Law of Slavery, and the Meaning of Manumission in Revolutionary and Early National Virginia.” PhD dissertation, Vanderbilt University, 2013.

Henrico County Court. “Henrico Co. Order Book (& Wills), 1678-1693.” Reel 53, page 163, 1684.

Henrico County Court. “Henrico Co. Order Book (& Wills), 1678-1693.” Reel 53, pages 326-327, 1690.

Kennon, Anne Hunt. “Theodorick Bland, Bland Papers, 1713-1825. Section 2.” Call number Mss1B6108 a20, 1763.

Kennon, Elizabeth. “Henrico County Miscellaneous Court Records, Vol. 4, 1738-1746”, reel 2, page 1225, 1743.

Kennon, Elizabeth. “Tom, etc.: Deed, 1759 (1108028_0018_0003. Virginia Untold: The African American Narrative Digital Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va.” Henrico County (Va.) Deeds, 1650-1931 (bulk 1813-1931), 1719.

Morgan, Edmund S. Virginians at Home: Family Life in the Eighteenth Century. Williamsburg, VA: The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1952.

No author. Slave Trading to Virginia. America In Class, National Humanities Center, https://americainclass.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/REV-Slave-Trading-to-VA.pdf.

Absolutely awesome! I keep learning new things about my ancestors from your research. Thank you so much.

Glad you enjoyed it Ann!!! I’ll keep it going as always. And thank you for the input you gave me as I was working on this, it was truly appreciated and helpful. Your views on things are, as always, valuable to me when I ask for your opinion on the topics and content.

T.

Very interesting!