The Will of Richard Kennon of Conjurer’s Neck

On 6 August 1694, Richard Kennon of Conjurer’s Neck (what was then Henrico County, in present-day Colonial Heights, Virginia), either wrote or dictated to another his will. Around this time, the bridge between the 17th and 18th centuries, the way wills in colonial Virginia were executed went through a change. In the 17th century, wills were composed in a less formal manner, kind of like two people were just sitting down having a conversation. Wills in 18th century Virginia shifted to a more formal, legalized, and structured format.

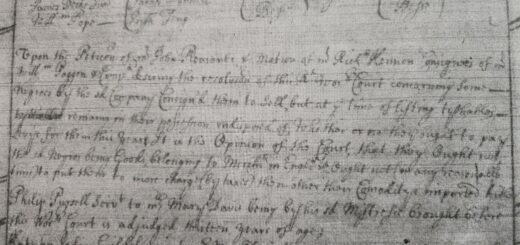

Richard Kennon’s will, courtesy Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

In 1700s Virginia, anyone over the age of twenty-one could make a will, except for married women. Women who were either unmarried or widowed, could make a will designating who received belongings. But if a woman was married, any land and property she had going into the marriage would become the husbands. There were exceptions to this. George and Martha Washington for example. Martha brought to their marriage one of the largest estates in the colony, including much land and many slaves. George managed Martha’s land and property, but said land and property belonged to the estate of Daniel Parke Custis, Martha’s first husband. So, upon her death, any land and property she owned would go to her children or grandchildren (George and Martha never had any children, so much of George’s estate went to his family). When it came to wills, many different types of bequests or stipulations could be put into the will.

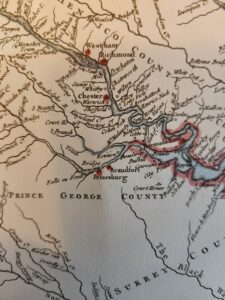

Part of the 1751 Jefferson-Fry Map of Virginia. Pictured in the center is the location Old Brick House, the Kennon family home.

Husbands would often designate that their wife could retain use of land, home, and belongings for the remainder of her life. After the passing of the wife, land (at least the best holdings, including the home plantation) would go to a first-born son; this was known as primogeniture. Other plots of land could be distributed to any other sons. Sometimes daughters could be willed land upon her marriage or when she reached her majority (in the colonial era, one reached their majority at twenty-one years of age). In many instances, daughters would be willed slaves and money when either she married or reached the age of her majority. Often, slaves, which were viewed as property in colonial Virginia, were willed to children or were instructed to be sold to pay off any debts.

It is not known when and where Richard Kennon was born, but it is known that in 1677, he purchased Conjurer’s Neck on the Appomattox River. Here he built a home for his family. Kennon was a very prosperous merchant in the colony and served in the Virginia House of Burgesses for Henrico County. He married Elizabeth Worsham in 1675. Old Brick House in Colonial Heights was the Kennon family home (see Jefferson-Fry map, the point marked Kennon is Old Brick House). Richard willed the house and land at Conjurer’s Neck, sometimes called just “The Neck”, to his wife, who passed it on to their only surviving son, William. William in turn, deeded the property to his own son, Richard. The house at Conjurer’s Neck would stay in the Kennon family until the late 1700s and would pass through a succession of owners. Old Brick House burned in 1879; only the North and South walls survived the fire, and the house was rebuilt around those remaining walls.

Richard Kennon’s will is as follows:

In the name of God amen I Richard Kennon weighing and considering my frailty and mans mortality being poor in and of sound and perfect minde & memory, praise be god hereby revoaking all former wills by me made doe make and ordaine this my last will and testament committing my soul into the hands of almighty god ________ and my body to the Earth with deacent buriall hopeing through the merritts of my lord saviour and redeemer Jesus Christ to have remission of my sins and enjoy full resurrecion at ye last day. and for my worldly Estate I dispose of as followeth I give and bequeath to my son William and his heirs for Ever. all that my plantacon and tract of Land called Roxdaile lying upon James River. and all that my mill and Land thereto belonging at Pucketts in Bristoll parish and my one halfe Acre of Land and housing thereon at Bermerdo (Bermuda) hundred all lying and being in Henrico County.

Item I give and bequeath unto my dear and loving wife Elisabeth and her heires for ever by me Richard Kennon as she shall think fit by [writing/working] to nominate & appoint all that my plantacon & devidend of land whereon I now live Called the Neck; and all that my plantacon and Tract of Land called the Quarter lying upon Swift Creek in Bristoll parrish in Henrico County aforesaid. Item I give unto my Daughter Judith one younge feemale Negro. All the rest of my Estate whatever after my Debts and funerall Expences paid & defrayed. I give unto my aforesaid wife to be disposed thereof as she shall think fitt and lastly I make and ordaine my sd. wife solo Exerx: of this my last will and testam.t In ____ whereof I have here unto put my hand & seale this sixth day of August one thousand six hundred ninety four; 1694

Published signed sealed

and delivered in presence of

Geo: Robinson

John Pigott Richard Kennon

Nich: Dison

Several things can be gleaned from Richard Kennon’s will. To begin with, one can see how religious he was considering the language used in the first several lines of his will. In colonial Virginia, all residents were required to attend church services. The Kennon family’s parish in their locality was Bristol Parish, which was founded in 1643.

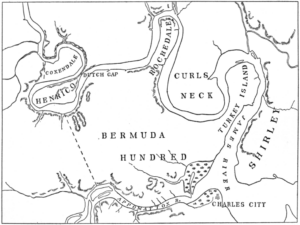

Richard and Elizabeth had a total of eight children, yet Richard only makes bequests to two of those children. It is known that some of those eight did not survive to adulthood. One child, Richard, was born in 1684 and died in 1688. Richard bequeaths to his son, William, land at “Roxdaile”, Pucketts and a half acre of land at Bermuda Hundred. The land he calls “Roxdaile” is the Rochedale, located near Bermuda Hundred (see both maps). William also received Conjurer’s Neck (likely through primogeniture), or “the Neck”, that his mother retained use of after the passing of his father. Pucketts was located near Conjurer’s Neck in Henrico County. The only other bequest Richard makes to one of his children is a female slave that he wills to his daughter Judith. This shows that the Kennon family, as many prominent tidewater families, purchased and used slaves to work their lands. How many slaves the Kennon family owned is unknown. Unfortunately, the ravages of war and time have left little documentary evidence to obtain more information on slavery regarding the Kennon family.

Map showing Bermuda Hundred and Rochdale, or “Roxdaile”.

Richard gives his wife, Elizabeth, use of and authority to dispose of Conjurer’s Neck and a plot of land called the Quarter on Swift Creek. At the end of the will, he names Elizabeth as the sole executrix of his will. Naming a wife the executrix of a will was not common, but also not unheard of in colonial Virginia. There were no laws barring women from executing the terms and stipulations of a will. The will is concluded with the signatures of Richard Kennon and those present at the recording of the will. Richard Kennon died sometime in 1696, as his will was proved in Henrico County court on 20 August 1696.

References

Breig, James. “Wills Simple and Elaborate: Bequests, Gifts, and Legacies.” The Colonial Williamsburg Journal. Accessed 11 July 2024. https://research.colonialwilliamsburg.org/Foundation/journal/Summer07/will.cfm#:~:text=In%20eighteenth%2Dcentury%20Virginia%2C%20anyone,when%20she%20died%20in%201785.

Kennon, Richard. “Virginia wills and administrations.” Part of index to Henrico County Wills and Administrations (1662-1800), microfilm, Deeds, Wills, Etc., 1688-1697 (reel 5), p. 651, 1696, Library of Virginia.

Awesome information, Todd. I gleaned some information from this.🤗

Cecelia, I wish that I would be able to find more information on Cicero, but with slavery being what it was, and how enslavers were, finding more information on Cicero is highly unlikely, unfortunately. But you never know, always gotta keep your eyes open, new information pops up sometimes.