Unknown to Known: How Cicero Gained His Identity

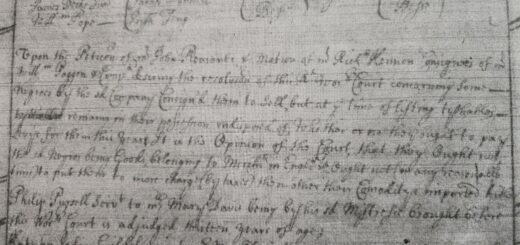

In the colonial era, documents mentioning enslaved persons are hard to come by, and even rarer are documents with details about the slaves themselves. Newspaper advertisements for runaway enslaved persons would often mention slaves by name and brief descriptions and what they may have last been wearing; this was the exception because at that time slaves were property, and only represented a financial commodity. Estate inventories and wills often mention slaves but they are not always mentioned by name, usually just their sex. Why is that? Because during the time that slavery occurred in the colonies and the early Republic, slave owners wanted to take every shred of dignity away from slaves. One of the ways they did this was by not mentioning them by name in documents, in essence taking away their identity. Sometimes one can find letters that may mention a slave by name, but usually only in regard to a financial transaction.

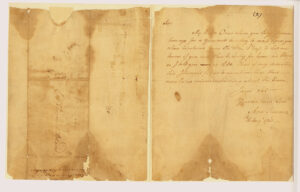

Several years ago, I went to the Virginia Museum of History and Culture in downtown Richmond to do some research on the Kennon family of Conjurer’s Neck in present day Colonial Heights. One of the sets of documents that I pulled in their research library was from the Bland Papers. In that collection, I found a letter from Anne Hunt Kennon to Theodorick Bland of Cawsons. Anne Hunt Kennon was the daughter of Captain William Hunt and wife of Richard Kennon, a grandson of Richard Kennon of Old Brick House, Conjurer’s Neck, Henrico County (now Colonial Heights).

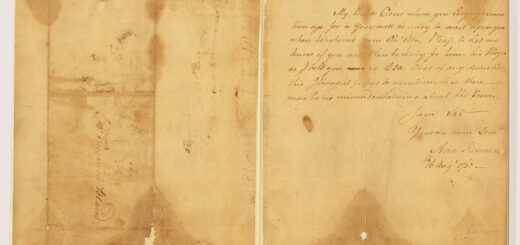

Letter from Anne Hunt Kennon to Theodorick Bland of Cawsons. Image courtesy of Virginia Museum of History and Culture (Mss1B6108 a20), www.virginiahistory.org.

A few wills of the Kennon men make mention of slaves gifted to sons and daughters, in some instances mentioning said enslaved persons by name. Richard Kennon, the founder of the family in the colony and owner of Old Brick House, makes a bequest to his daughter, Judith, “one younge feemale Negro.” The Kennon family were heavily involved in the purchase of numerous enslaved men, women, and children. How many slaves the different generations and branches of the family owned is unknown, as not many documents show their total holdings of enslaved people.

As I read the letter Anne Hunt Kennon wrote to Theodorick Bland, the content of the letter stuck out to me immediately. The letter gives a little bit of a glimpse of the role the Kennon family played in the institution of slavery. Though the letter is short, much information can be gleaned from it:

Sir,

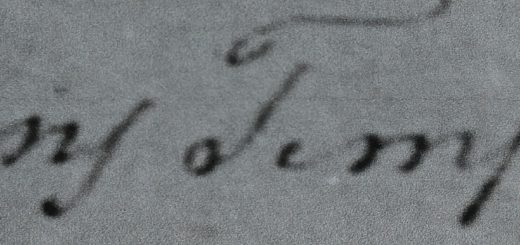

My Baker Cicero whom you Engagd some time ago for a Year will be ready to wait upon you when he returns from Ch City, Please do Let me know if you will then be ready for him. his Wages as I told you is £30. Clear of any deduction this I thought proper to mention, that there may be no misunderstanding about the Terms.

I am Sir

Your mo hum Servt

Ann Kennon

th16 Augt 1763

The first thing that stood out to me with this letter was “Cicero”. Anne mentioned her slave by name, she gave him his identity just by writing his name. But it is important to remember that slaves, in most instances, did not get to pick the names they gave their children, or their own names when they came to the colonies. The name Cicero itself follows a pattern of how enslavers named their bondspeople in the 17th and 18th centuries. Many slaveowners would name their slaves after Greco-Roman characters, heroes, and authors. Susan Wegner, an Associate Professor of Art History and Chair of Department of Art at Bowdoin College, states that enslavers naming their slaves after “classical names could show off slave-holders’ learning while also mocking those humans held as property by giving them ironic names of powerful ancient rulers, gods, and heroes.” Some of the names enslavers gave to their women bondspeople, like the name Venus for example, “reflected and licensed the lasciviousness of European slaveowners toward African women, making such behaviors ‘sound agreeable,’” states Sarah Abel, a cultural anthropologist.

In some cases, white enslavers would trick the enslaved into naming a child after a white person. A case in point is Dolley Madison, wife of United States President James Madison, and Sally Hemmings, Thomas Jefferson’s slave who he fathered six children with. When Sally was pregnant with her son Madison, Dolley Madison promised Sally a gift if she named the child Madison. Sally, expecting some sort of gift in return, named her son Madison. No gift was ever received for having done so.

Cicero was a baker, a skilled position in colonial era slave society. Though being a baker was a more ideal job than having to work in a field from sun up to sun down, no matter the weather, it was still a tough job. Early on, kitchens were attached to homes, but later, to prevent fires to the main house, kitchens were later built as separate buildings. They were often hot as a fire was almost always burning in the kitchen fireplace and stoves. On a hot summer day, that would have made for an uncomfortable work environment. The work of being a cook or baker was physically demanding as well.

In the colonial era slave society of the Kennon family, hospitality was the word of the day. Guests were always coming by for visits; usually for a day but sometimes as much as a few days to possibly weeks. To properly provide for guests, prominent families planned big meals. To have a good cook and baker made this possible. Meals were a big to do. Dinner, the largest meal of the day, was usually served around two or three in the afternoon. The meal at dinner time could include many different types of fruits and vegetables, and several different types of meats. Pastries, breads, and desserts would be made throughout the day for all meals. A cook and baker would likely be in the kitchen well before sun-up until the end of the day.

How good of a baker was Cicero? I would venture to say he was a very skilled baker, as the letter alludes to the fact that he had previously been hired out to Mr. Bland for the term of a year. Anne Hunt Kennon mentions that the term for hiring him out would be £30, not a small sum (in today’s U.S. dollars, the amount would be $7, 586.69), even in 1763.

Although his white enslavers gave him an identity in the letter, there is so little detail known about Cicero and his life. It is therefore important that he be given dignity by thinking about the human that he was. Did Cicero ever have a wife and children? If he did, unless his wife was free, any children would have been born into the system of perpetual bondage. Are there any living descendants of Cicero? Did he ever see a day when he became free (likely not as very few Virginians emancipated their slaves)? How did Cicero feel about his position in life? Did he yearn to be free someday? Answers to these questions may never be known. There may be more information about Cicero that has yet to be found. But the finding of this letter, mentioning his name and occupation, gives him an identity and humanity in a system that attempted to stamp out both. He played a big part in the progression of southern foodways, which still has a big influence in today’s southern cuisine. Hopefully, more future research will turn up more answers about who Cicero was, if he had a family, maybe even a written description of him. Only time will tell. The institution, the system, tried to make him an unknown, a nobody, but the few written sentences in Anne Hunt Kennon’s letter made him somebody, they inadvertently gave him and identity and a story.

References

Kennon, Anne Hunt. “Theodorick Bland, Bland Papers, 1713-1825. Section 2.” Call number Mss1B6108 a20, 1763.

Morgan, Edmund S. Virginians at Home: Family Life in the Eighteenth Century. Williamsburg, VA: The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1952.

Wegner, Susan. “Classical Names and Concepts Used in the Service of Slavery.” Bowdoin College Museum of Art. Accessed 24 July 2024. https://bcma.bowdoin.edu/antiquity/classical-names-and-concepts-used-in-the-service-of-slavery/.

Very interesting!

Great find Todd of Cicero! I would love to know more about him!

Kay, it was a fun article to research and write about. Maybe with more research, I may be able to find more information. Unfortunately though, it’s likely that this is all the information we’ll be able to find about Cicero.

Very informative! I enjoyed this article and look forward to more!

Glad you enjoyed it, Wanda!!!